July 20, 2020

Guest post by David Popp, Ziqiao Chen and Hossein Hosseini

This post is part of Smart Prosperity Institute’s Smart Stimulus Project and supports the work of the Task Force for a Resilient Recovery. Want to receive our latest analysis and insights? Sign up for our monthly updates here.

Nations around the world - including Canada - have shut down large portions of their economies in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Government spending will be important to both maintain the economy during these shutdowns and to help restart it as restrictions are lifted. Many proposals for pandemic-related stimuli include calls for a “green” stimulus (e.g. from the International Monetary Fund, International Energy Agency and the European Union) that both restarts the economy and helps it transition to a cleaner, more sustainable path.

The effect of green spending in the 2009 US stimulus in response to the Great Recession is studied by Francesco Vona, Giovanni Marin, Ziqiao Chen and David Popp in two recent working papers, focussed on the employment impact of a green fiscal push and the role of skills for a resilient recovery. This stimulus included several programs designed to promote clean energy and green jobs, such as investments in renewable energy and energy efficiency retrofits (Aldy, 2013). We find that the green stimulus did increase overall employment, but nearly all the effect was in the long-run (2013-2017). Providing funding programs that match the skills workers have is important. These results provide guidance on the role green investments can play in economic recovery.

For any pandemic-related recovery, the first priority should be to restart the economy. While a green stimulus can help reshape the economy, it is less likely to help restart the economy. To put limited government funds to the best use, initial rounds of a post-pandemic stimulus should prioritize investments that get people back to work quickly. Our estimates of slower employment stimulus response from green investments differs from studies of other types of stimulus projects (such as construction and transportation) which find significant short-run (i.e. in first 3 years) job creation (e.g. Wilson 2012, Garin 2019). Such investments should take first priority.

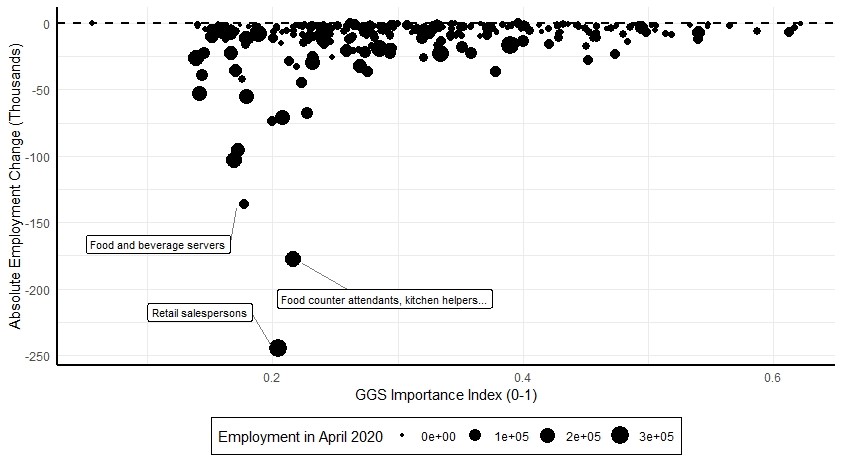

Ideal stimulus spending is not “one-size fits all.” Providing funding for programs that match workers skills is also important. In the US, the 2009 green stimulus increased employment in communities where workers had the skills necessary to work in green jobs: skills such as engineering, operations management, and science. In our newest working paper, we compare the skills needed in high-demand green occupations to skills in jobs most at risk of disruption from COVID-19. In Canada, the largest job losses were in occupations making little use of green skills, such as sales and service (see Figure 1). These workers will not benefit from a green stimulus. Instead, stimulus investments could help reduce the risks that workers in these jobs face, such as by providing technology and security equipment (e.g. masks, plexiglass barriers). Such investments should aim to both make it easier and safer to return to work, and to also give potential customers confidence in the safety of using these services.

This does not mean that green investments have no role to play in a pandemic-related recovery. Interestingly, one group of workers in possession of the skills needed to benefit from a green stimulus are those in “brown occupations”, such as the oil and gas industry, who have experienced job losses due to falling energy prices. Most occupations in these sectors use engineering skills that are also prominent in green jobs. In fact, the main fossil-fuel producing provinces in Canada (i.e. Alberta and Saskatchewan) have a higher than average presence of green skills. Because related green jobs, such as installing or servicing renewable energy sources, require over a year of on-the-job training, some training will likely be required for workers transitioning from these brown jobs into green jobs. However, the similar skill set for these workers provides hope that training will ultimately be successful.

Finally, our long-run results show that green investments can help “reshape” the Canadian economy. These investments are important for Canada to maintain its commitment to a net-zero carbon economy by 2050. Moreover, the COVID-19 crisis may trigger long-term structural transformations in the economy that are largely unpredictable now. For instance, might demand for fossil fuels remain low as business travelers realize the potential of replacing face-to-face gatherings with video conferencing? Will oil prices ever return to a level profitable for oil production in western Canada? Stimulus planning should prioritize creating an economy that will be sustainable in the long run. Bringing workers back to jobs in industries soon to become obsolete is not a good long-term investment. Several rounds of public investment will likely be necessary once the pandemic ends. It would be irresponsible for politicians to confuse the short-term and long-term needs of recovery and tell the voters that a green stimulus is going to magically bring back all jobs. That said, it is also irresponsible to argue that the current crisis allows us to ignore the ongoing pollution and climate change crises.

Learn more: read David Popp’s previous guest blog on how government investments can smooth worker transitions in a green economy, but must be used carefully.

This blog is based on a recent Smart Prosperity Clean Economy Working Paper titled “Green stimulus in a post-pandemic recovery: the role of skills for a resilient recovery” by Ziqiao Chen, Giovanni Marin, David Popp and Francesco Vona.

The Clean Economy Working Paper Series disseminates findings of ongoing environmental and clean economy work conducted by researchers from a range of disciplines including economics, public policy, political science, and law.