October 19, 2021

Guest post by Deishin Lee and Jury Gualandris

Why are reverse supply chains so difficult to implement? We have supply chains for everything -- cars, food, computers, violins, toilet paper ... they all (usually) work amazingly well. And when there are supply disruptions, industry, governments, and media shine a spotlight on the problem to get goods flowing again. However, when it comes to the supply chain that takes end-of-life products and transforms them into new materials and products (i.e., the "reverse supply chain"), it's a different story. Why?

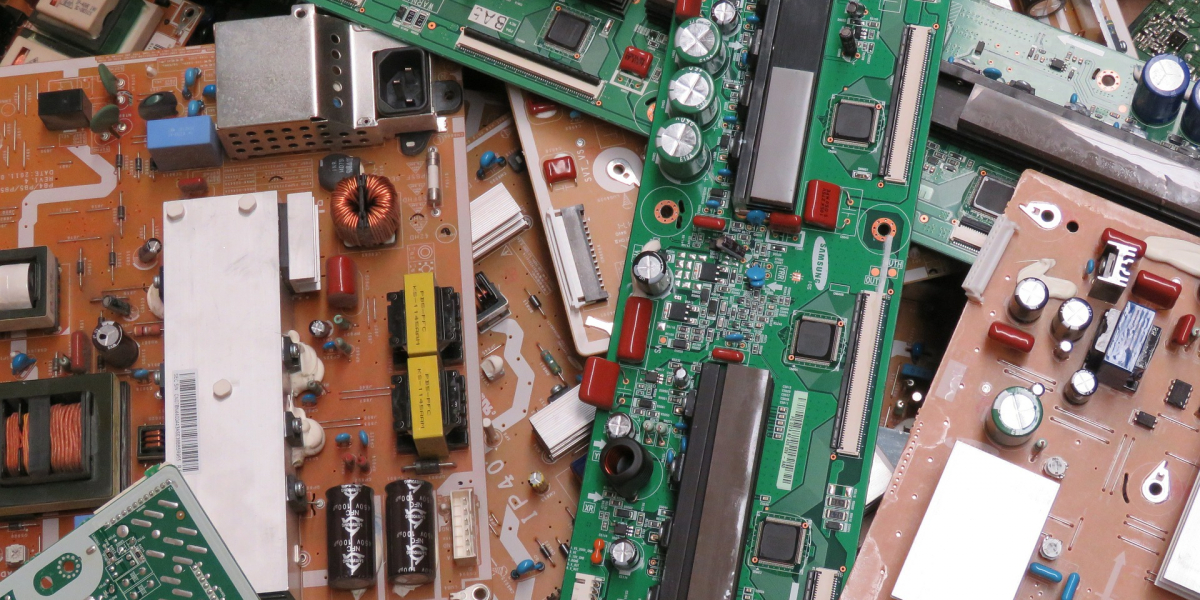

One obvious answer is that reverse supply chains are notoriously difficult to implement: collection, recovery and recycling of end-of-life products is a nightmare -- people stuff their closets full of things that could be recycled, and when they do dispose of these items, they comingle the recyclable items with non-recyclable ones, or they throw them in impossible places making the collection process more like a scavenger hunt. Even when a recycler is able to source end-of-life items, they have to figure out how to reverse the steps taken to create the product -- steps that were typically designed to make breaking apart the product as difficult as possible. Our new Smart Prosperity Institute working paper details the key logistical and operational challenges that characterize collection, recovery, and recycling processes in the reverse supply chain.

That said, firms have previously not shied away from difficult tasks. Think of the monumental efforts of science, engineering, and human creativity required to produce semiconductor chips, aircrafts, and skyscrapers -- things we now take for granted as achievable. Our industrial system is clearly capable of extraordinary feats. The Extended Producer Responsibility movement is intended to harness the capabilities of firms – those who created these end-of-life products in the first place – to mitigate the unintended consequences of their (forward supply chain) ingenuity. To further strengthen the link between producer and end-of-life responsibility, in Ontario, Extended Producer Responsibility has shifted to Individual Producer Responsibility. Each individual producer (instead of the industry as a whole) is responsible for collecting, recovering, and recycling a portion of the end-of-life products they supplied within the province. Untangling the practicalities of how this works requires administrative support to design, monitor, and verify that reverse supply chain activities are executed appropriately. In general, regulators use the Extended Producer Responsibility/Individual Producer Responsibility instrument to mandate how producers should address the end-of-life product waste problem.

However, there is another key difference between forward and reverse supply chains that hampers the development of thriving reverse supply chains. In contrast to forward supply chains, the demand for recycled materials and products made with recycled materials -- the output of reverse supply chains -- is weak and inconsistent. Often, recycled materials have to compete with virgin materials whose price does not incorporate the cost of negative externalities such as pollution from extraction, landfilling, and potential leakages – effects that reverse supply chains are expected to mitigate. Virgin material quality and delivery can also be more consistent -- at least initially, when the reverse supply chain is in the early stages of development. If no one is asking for recycled materials and products, then no one will shine a spotlight on reverse supply chains that don't work or don't even exist. Extended Producer Responsibility/Individual Producer Responsibility instruments focus on the how and do not address the (lack of) demand for recycled materials – as we explain in our working paper. This is a fundamental problem because market demand motivates firms to innovate, often beyond what is strictly required by regulation. If we mandate the creation of supply chains to produce something, someone should want to use the output. Therefore, as a complement to Extended Producer Responsibility/Individual Producer Responsibility, we need to figure out a way to generate demand for recycled materials and products. Some companies have unilaterally taken the initiative to support recycled materials (e.g., HP sets internal targets for recycled plastic content). However, regulators could do more to mandate minimum recycled content or use their own purchasing power (i.e., public procurement) to provide a market for recycled material. A shift to bolster the market for recycled material is expected to spur innovation in the reverse supply chain -- something that firms are good at. When there is a healthy demand for a product, supply chains usually have a way of working themselves out.

To learn more, check out the full Smart Prosperity Institute working paper on Policy-driven Innovation in Reverse Supply Chains for Post-consumer Plastic in Packaging and Electronic Waste.