March 26, 2021

By Teslin Augustine and Harshini Ramesh

Following COVID-19, there have been calls for a green recovery that takes into account both the economic and environmental impacts of spending decisions. What is often missing in these discussions, however, is an analysis of the health impacts associated with these green recovery approaches.

Assessing the health impact of recovery investments involves going beyond the direct physical or psychological impact of spending decisions, and thinking about how these decisions impact individuals’ ability to be healthy. It involves considering how recovery spending affects the physical and the socio-economic context of an individual. In other words, a more holistic assessment of the health benefits associated with a recovery project requires thinking through how recovery spending will service long-term goals of reducing social inequalities and how it will mitigate health inequities in our society.

To advance the inclusion of a broader health lens in a green recovery, SPI is exploring an array of recovery projects and the health dimensions they impact to better outline what considerations are necessary to ensure an inclusive and healthy recovery. While the findings of this research will be detailed in an upcoming report, this blog provides an overview of how to frame a more fulsome understanding of health in the context of recovery projects.

Previous SPI blogs have highlighted the value of incorporating health considerations in spending decisions and have talked about how incorporating a health lens is important for assessing the true costs and estimated benefits of green recovery investments. In the context of recovery spending, the health impact of proposed policies or projects is often framed as a health ‘co-benefit’. A health ‘co-benefit’ is the ancillary positive health effect of policies, projects or programs aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, supporting greater environmental conservation, or supporting cleaner economic growth. For example, a health co-benefit associated with investing in expanding public transit would be improved air quality and lower incidence of asthma.

However, transit expansion has other health benefits too. Access to public transit increases an individual’s ability to access healthcare services and other things necessary to lead a healthy and full life. This is especially true for areas categorized as transit deserts, wherein individuals lack access to proper transportation and infrastructure due to investment failures. Therefore, simply relying on a health co-benefits assessment for understanding the potential benefits of transit expansion doesn’t represent the complete picture.

While the debate on how best to define health is not yet settled, the days when health was seen simply as the absence of disease or mortality are long gone. It is now widely accepted that health is a broad concept that encompasses physical, mental, and social well-being, as well as quality of life. A more fulsome approach to health considers living conditions, societal, and economic factors as influential to population health.

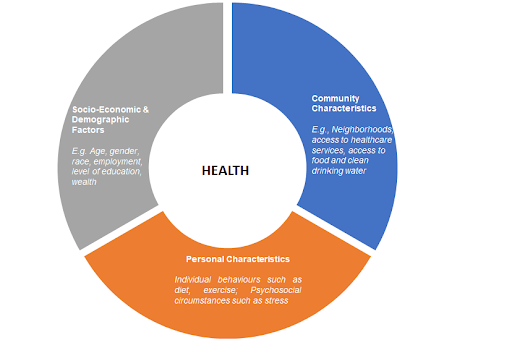

Individual health is seen as being influenced by four main factors. First, personal characteristics including genetic composition and behaviours such as diet, exercise, alcohol, or tobacco consumption, and psychosocial circumstances such as stress and coping styles impact health. Second, socio-economic and demographic factors such as age, gender, race, level of education influences health. Finally, community characteristics such as neighbourhoods, access to healthcare, access to green spaces, and larger systems level factors such as labour policies, cultural norms and other macroeconomic factors impact health. Therefore, a more precise analysis of the public health impact of recovery spending will consider not just the direct physical or psychological impact of policies and programs, but will also consider how it affects the physical and psychosocial circumstances, as well as the system-level and community features of an individual.

A discussion about health would be incomplete without also understanding the role health equity plays in determining peoples’ ability to be healthy. The WHO defines health equity, as the “absence of unfair and avoidable or remedial difference in health among social groups”. The conditions in which people live, study, work, the quality of their communities, their interaction with their health, social service, and educational institutions all affect health.

Accepting this reality carries with it the acknowledgment that some Canadians simply have more opportunities to lead a healthier life than others. Studies have confirmed disparities in life expectancy amongst Canadians depending on income and level of education. Those with higher levels of income or education have a longer life expectancy and are more likely to spend a greater portion of their lives in good health. Therefore, understanding that health equity underpins health helps explain health disparities between communities by analyzing their physical, social and economic environments.

The recovery spending decisions that Canada makes today will shape its future in the coming decades. A holistic view to spending addresses not only a resilient recovery but also its health implications. Health is a complex and multi-dimensional concept and examining the green recovery discussion from this perspective changes the way we approach spending decisions. It also highlights the importance of equity and inclusivity to the forefront. This broader conceptualization of health changes how we assess the potential costs versus benefits of a project, and ultimately which projects are included in the recovery discussion, especially when considering who is most impacted by the decisions made.