August 20, 2024

The Government of Canada is counting on zero-emission vehicles (ZEV) to benefit the environment and the economy. All new light-duty vehicles (cars, SUVs, some pick-up trucks) sold in Canada will need to be a ZEV by 2035, with federal targets of 1.4 million ZEVs on the road by 2026, rising to 4.6 million by 2030, and 12.4 million by 2035. The federal 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan estimates that these changes to transportation from 2005 to 2030 will result in an 11% reduction in emissions and benefit future generations. But it is not enough to simply require that gas powered vehicles be replaced with electric ones for drivers to accept and buy a ZEV. There are risks of greater resistance to ZEVs, the current inability for a third of Canadians to adopt one, concerns that consumers will see them as an expensive hassle, and the missed opportunity of plug-in hybrids not living up to their electric potential. Achieving our net-zero targets will require charging infrastructure be built strategically at a pace that will allow more Canadians to embrace ZEVs and that can keep up with the projected ZEV adoption.

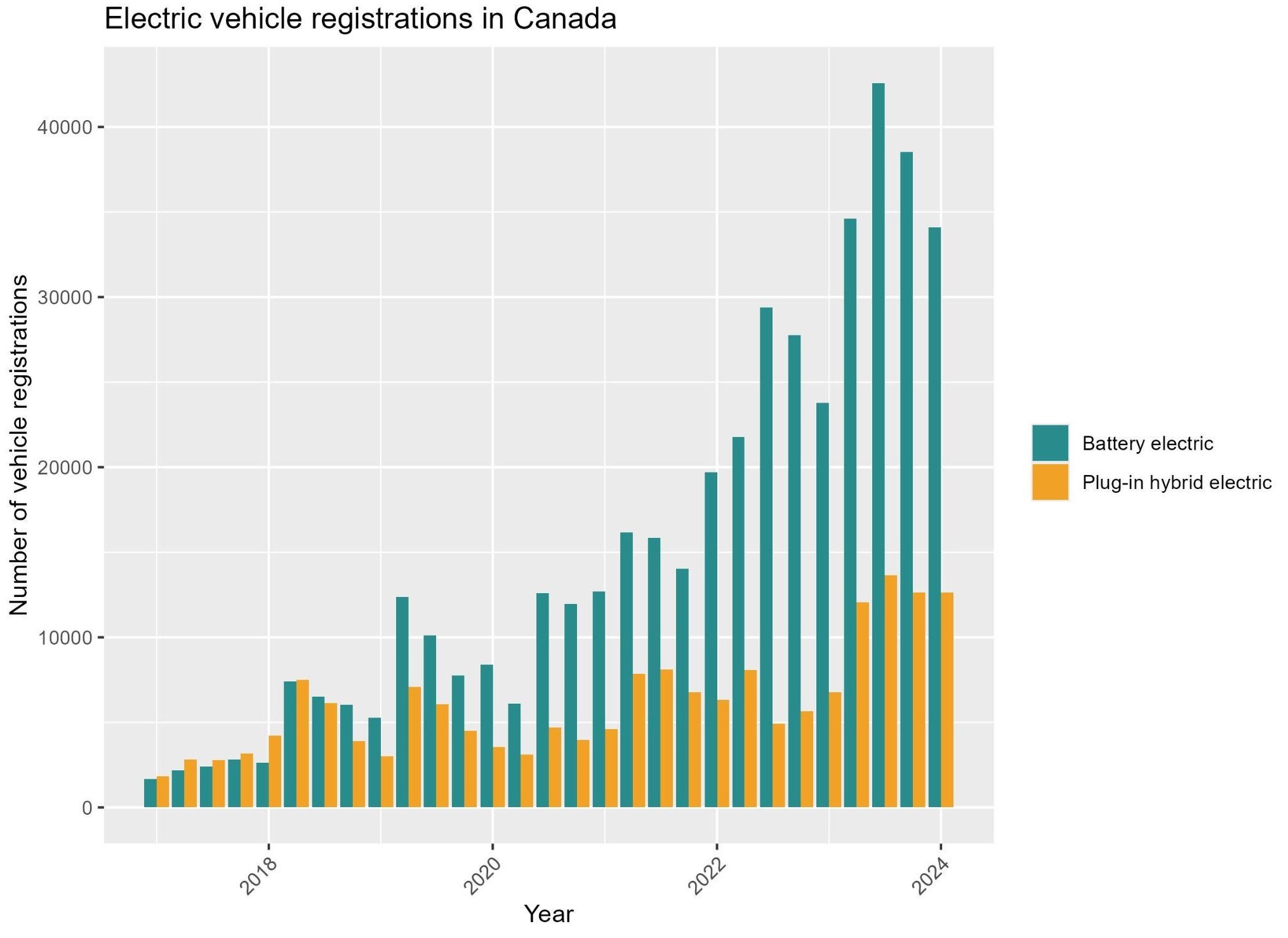

There is some positive movement, as battery electric vehicle (BEV) registrations are outpacing plug-in electric hybrid vehicles (PHEV) in Canada (Figure 1). However, at least one-third of Canadians face major barriers to adopting a ZEV. This includes citizens that live in apartments/condominiums, dwellings without a driveway or garage, older homes, and rentals because of a limited ability or inability to charge at home combined with a shortage of public chargers in the area, referred to as a charging desert. These Canadians are unlikely to buy a BEV or charge their PHEV enough to take advantage of its electric, zero-emission side. Increasing the availability, reliability, and accessibility of public EV charging infrastructure, specifically stations and ports, will be required for the federal government’s projected all electric, net-zero future and full adoption by Canadians.

Figure 1. ZEV registrations in Canada over time.

Data from Statistics Canada.

Federal investments towards public EV charging infrastructure include the Electric Vehicle and Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Deployment Initiative, which contributed to over one thousand fast chargers along Canada’s highway system, and the Zero Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Program (ZEVIP), which partially funds charging and refuelling stations. Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) gave $265.9 million through ZEVIP for 353 charging infrastructure projects between 2019 and 2023 and this program is still open. Keeping up with this momentum, Federal Budget 2024 promised over $1 billion to ZEVIP and the Canada Infrastructure Bank in total to be spent on improving access to EV chargers and EV affordability, with a goal to install 84,500 chargers by 2029. Will this be enough to build an extensive charging network to support Canada’s goal of 12.4 million ZEVs by 2035?

Investments in public charging infrastructure must be strategic and prioritize building and maintaining sufficient chargers, reliable networks, and a smooth user experience.

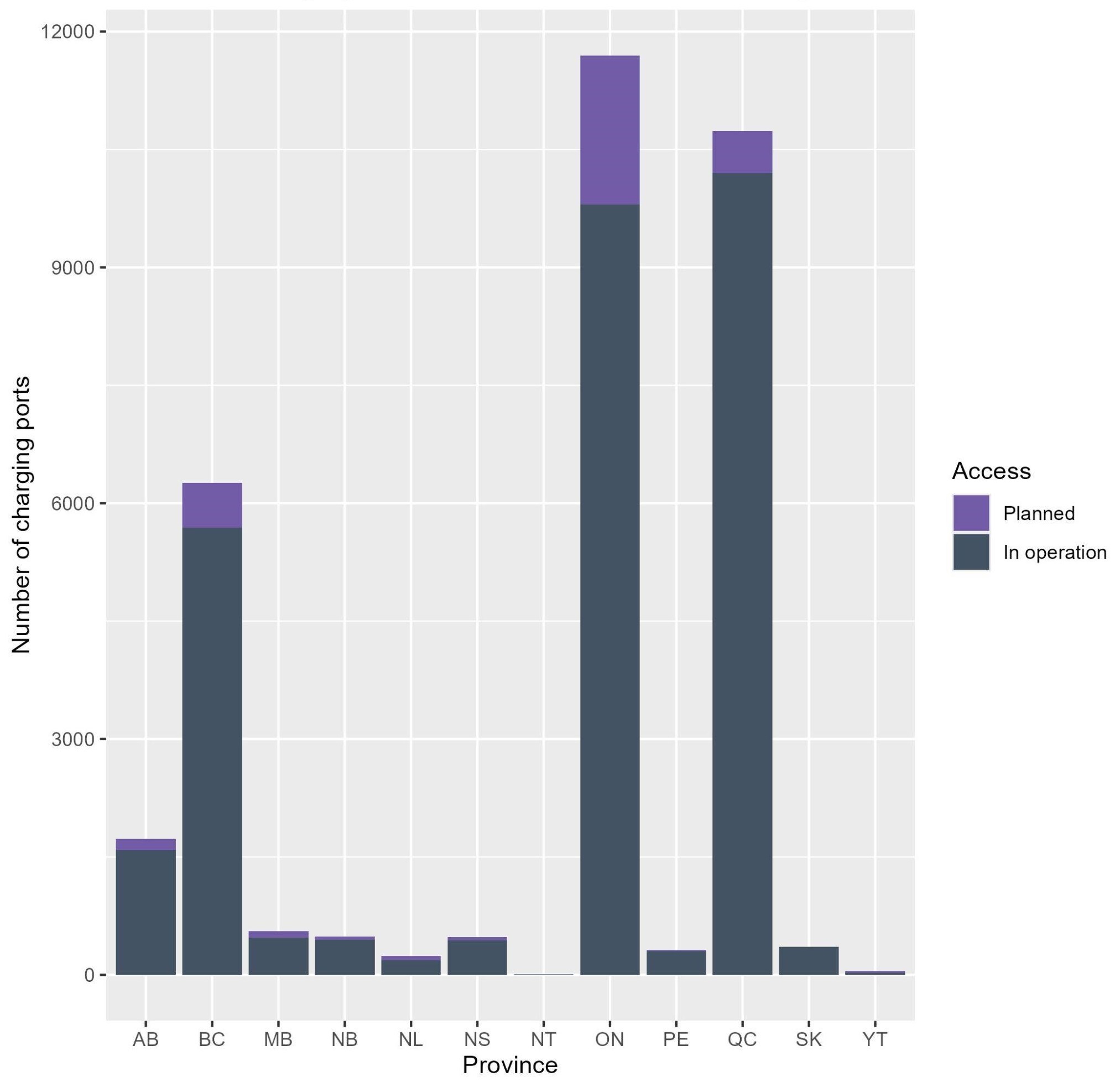

Sufficient and widespread number of chargers

Charging deserts across Canada are a major issue (Figure 2), contributing to range anxiety, and a primary reason Canadians decide not to purchase an EV. According to the Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers’ Association’s CEO, a shortage of charging stations is the greatest challenge to the federal mandate that all new light-duty vehicle sales be ZEVs by 2035. Although the amount of public EV charging ports has tripled since 2018 and there are now almost 33,000 Level 2 and DC Fast charging ports available, many provinces still lack supply (Figure 2), with even fewer charging options in remote areas. As of 2023, ZEVIP funding resulted in 29,407 charging ports built in Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec but only 4,480 ports in the rest of the provinces and territories combined. To increase access and usage, new charging ports should be spread throughout Canada, include rural areas, and be convenient. For example, Flo is installing over 500 Ultra fast-charging ports (80% battery within 15 minutes) at 130 grocery stores in Quebec and Ontario. Projects for over 25,000 EV chargers have been approved and funding is still being allocated, but these will take a while to be operational.

Figure 2. Planned and operational public EV charging infrastructure in Canada as of August 2024.

Data from Natural Resources Canada’s Electric Charging and Alternative Fuelling Stations Locator.

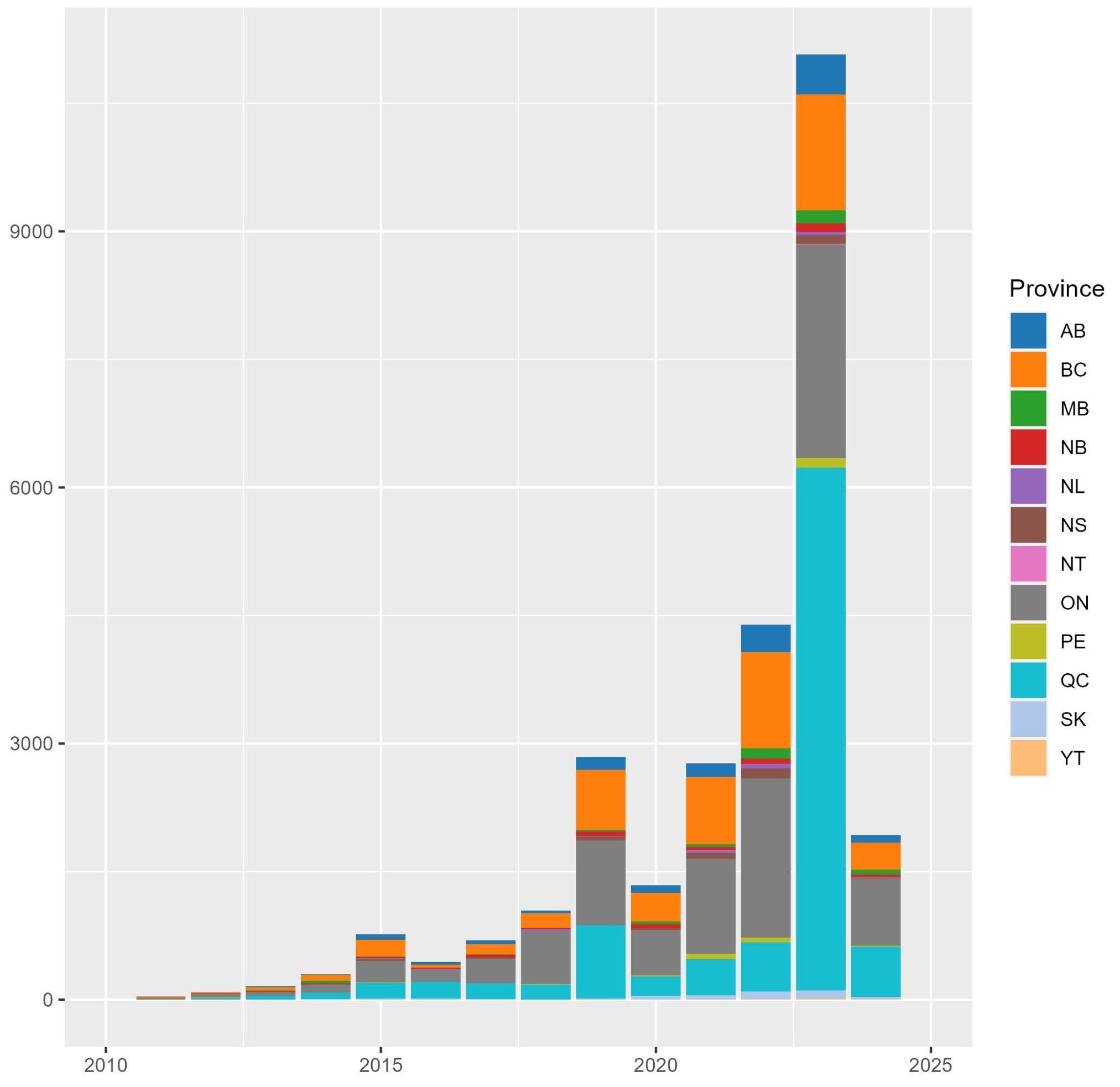

Provincial governments are also acting to increase the number of EV chargers, such as Ontario, which has promised $91 million and a Rural Connectivity Fund (where rural municipalities apply for funding to build local EV chargers). Quebec’s Electric Vehicle Charging Strategy shows their plan to have 116,700 public fast-charging and Level 2 charging stations by 2030. This strategy and subsequent investments are likely the cause of Quebec’s significant 2023 lead in building EV charging infrastructure (Figure 3). Other jurisdictions should look to Quebec when designing their own EV charging infrastructure plans and strategies.

Figure 3. New public EV charging ports in Canada per year.

Note: this figure was created in April 2024 and NRCan tracks EV charging infrastructure built using public funding. Data from Natural Resources Canada.

The federal government is aiming for 12.4 million ZEVs on the road by 2035. Updated research commissioned by NRCan states that Canada will need a baseline of 679,000 public charging ports by 2040. There are currently almost 33,000 available public fast charging ports. Thus, the installation pace must substantially increase to 40,000 public ports per year from 2025 to 2040 to keep up with the projected EV adoption numbers. Additional investments will likely be required to fund the building and maintenance of all of these charging ports.

Reliable networks

EV drivers will need to use public chargers when travelling on longer trips. Upon arriving at a station, several factors could still limit the ability to charge. If ports are occupied, new arrivals must wait an unknown amount of time to start charging their vehicle. Even if the driver has planned out their trip and specific charging stops, the chargers might not be operational and could take weeks or months to be fixed. For example, a 2023 survey found that EV owners experienced network outages 19% of the time in Quebec and up to 44% in other provinces. These problems tend to be worse when travelling long distances, although this is still frustrating in the city. The freedom of having a personal vehicle that produces zero emissions evaporates when drivers cannot charge their car and this disincentivizes EV adoption. The next round of ZEVIP funding aims to improve charger reliability by allowing funding to be used for pre-paid expenses and requiring charger uptime data to be tracked and publicly available. Programs in other countries also have station uptime requirements, such as 99% in the United Kingdom and 97% in the United States, but ZEVIP’s mandate and capacity would need to be strengthened for the same requirements to be implemented here. Ultimately, more EV chargers must be built throughout Canada (Figure 3), beyond major cities in Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia, and they should always be in working condition.

Smooth user experience at charging stations

Other aspects of usability may deter drivers from getting a ZEV. A charging session can be more complicated than expected because there is no standardization across charging ports. For example, not all chargers accept just card payment - there are multiple charging networks in Canada that often each require an account or even their own smartphone app. Multiple accounts to remember can be frustrating, especially since apps can have bugs that limit usability, and security concerns are raised by each app requiring payment details. Some networks are working to make this a simpler experience by offering Plug and Charge service. Another issue for drivers is locating a charging port type that is compatible with their EV model. However, efforts are being taken to address these issues such as Tesla’s North American Charging Standard essentially becoming the default for new ZEVs, certain adapters being made available for older vehicles, and Tesla’s Supercharging network becoming usable with a CCS connector. Companies should continue to prioritize these advancements, streamline and standardize the charging process, and allow drivers to simply plug and charge their vehicle.

Canada has strong target numbers in place for universal ZEV adoption and more public charging stations are being built thanks to various investments, helping to reduce our emissions and ultimately contributing to the overall goal of net-zero emissions by 2050. However, improvements around building enough charging ports and providing more equal access are still needed. Additional resources like government funding mixed with private capital will be required to achieve a sufficient amount of public, well-maintained charging ports in all regions across Canada. Charger uptime standards could be implemented and accessible charger maintenance courses could be provided to improve reliability. Lastly, innovations around interoperability and effectiveness and streamlining to deliver a smooth user experience must continue. Electric vehicles are the future and the accompanying supporting infrastructure is vital to increase adoption and usability.