June 14, 2019

By Dave Sawyer

As the politicization over climate policy rises with the upcoming election, there is an increasing need for a sound information base to unpack Canada’s progress towards its greenhouse gas (GHG) target. Central to taking stock of GHG progress to 2030 and beyond are emission projections. Canada has been producing emission projections for over ten years, providing a touchstone to assess Canada’s emission trajectory.

Emission projections are complex and speculative pieces of analysis and modelling, with many assumptions and drivers impacting the certainty that the forecasts will approximate actual emissions. Significant uncertainty is inherent in any exercise that forecasts emissions to 2030 while accounting for economic growth and market interactions, technological deployment and innovation and global commodity trends. Projections must also account for diverse national and sub-national carbon policy targeting diverse energy end-uses and technologies while predicting human behaviour out to 2030.

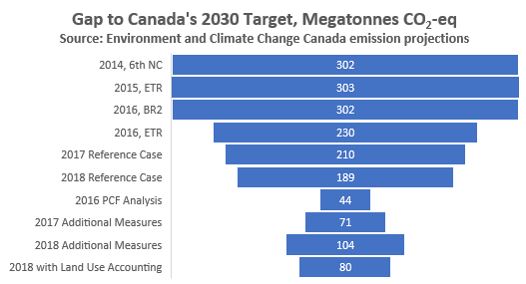

In practice, it is difficult to track commodity prices that can swing daily, yet we seem to take the central emission projections for 2030 with considerable confidence. Take, for example, the 2017 change in the forecast gap of Canada’s 2030 emissions target that showed a 22 Megaton (Mt) shift relative to the 2016 forecast of a 44 Mt gap.1 The 22 Mt change in the 2030 projection represented just 3% of the forecast 2030 emissions on a reported uncertainty range of over 93 Mt. Yet the 22 Mt shift was reported as a 50% backslide on progress. In 2019, the increase in the 2030 gap of 12 Mt was also reported as a backslide.

Despite the backsliding characterization in the press, successive federal GHG forecasts show progress towards closing the emission gap to Canada’s 2030 target. Prior to 2016 when the Paris agreement catalyzed both federal and provincial action, the gap to Canada’s 2030 target was forecast under Prime Minister Harper to be 300 Mt. As more policy emerged in 2016 in response to the Paris climate negotiations, the projections dropped over 70 Mt reflecting efforts by some provinces and the federal government to reduce emissions. While the federal government’s GHG forecast in 2017 showed a gap of 189 Mt, a federal assessment of the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (PCF) indicated a gap of 44 Mt if all measures were implemented as announced. Independent analysis of the PCF at the time verified that this was a reasonable forecast assuming all policies were implemented as described. Analysis by the Pembina Institute pegged the gap under the PCF at 161 Mt or 4 times what the government reported. While this result is being used politically as evidence of the failure of the PCF and carbon pricing in particular, the Pembina estimate was likely flawed and has subsequently been revised downward by 114 Mt to a gap of 47 Mt.

The 2017 and 2018 Reference Cases with forecast gaps of 200 Mt, by convention, did not report developing policies that had been announced but not implemented. When these additional policies or measures are added, including the Federal Clean Fuel Standard, carbon pricing in backstop jurisdictions and additional energy efficiency regulations, the gap is more than cut in half. This then is the better forecast of Canada’s gap, reflecting policies that are under development but by convention are not included in the published Reference Cases.

Despite the political rhetoric of late, Canada collectively has made progress on bending downwards our national emissions. Prior to a resurgence in climate ambition in 2016, the gap to our target was 300 Mt. As federal and provincial policy has been announced and implemented since 2016, the emission projections show a reduction in over half of forecast gap to Canada’s 2030 target. While these projections were made under both Conservative and Liberal governments, the core group of federal modellers remains largely unchanged, making apples to apples comparisons of the projections possible. Of course, with provincial governments unwinding carbon policy, notably in Alberta and Ontario, we can expect the gap to Canada’s 2030 target to grow. Ontario’s withdrawal from cap and trade under the Western Climate Initiative and its Climate Action Plan likely added 23 Mt of more GHGs to Canada’s latest 2030 forecast. It is politicization that continues to be the tempest that tosses Canada’s “steady as she goes” approach to what is an achievable and highly necessary low-carbon transition.