August 9, 2019

On August 8th, the IPCC released a special report discussing the role of forests and lands in absorbing or emitting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The report explains that the world will not be able to limit global temperature rise to below 2 degrees Celsius without government climate action in the land and forests sectors.

Here are a few examples (out of many) of what can be done here in Canada:

1) Continue to reduce deforestation rates

The IPCC report finds that the largest potential for reducing emissions from the land sector would come from curbing deforestation and forest degradation. Although Canada has one of the lowest deforestation rates in the world (with a loss of 0.02% of its total forested area annually), this still represents large areas of forests lost each year. In 2017 for example, 36 000 hectares of forest were permanently lost. This is an annual loss roughly equivalent to the size of Montreal. This permanent conversion does not include forests that are managed and harvested for timber resources, nor does it include forests damaged by pests or forest fires.

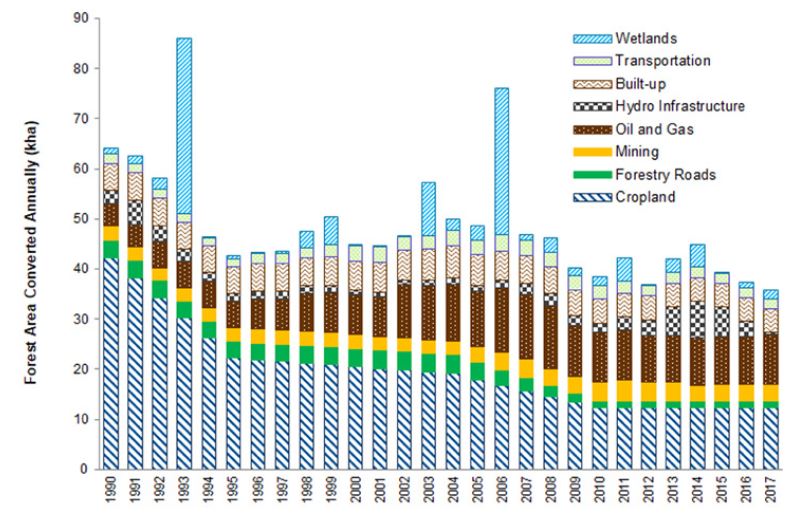

Canadian deforestation accounted for 11 million tonnes (Mt) of GHG emissions in 2017; to put this number in perspective it represents more emissions than all domestic aviation which stood at 7Mt in 2017. Forests are lost for a number of reasons – historically, agriculture has been the primary driver of deforestation, but the share of forests lost to resource extraction has been growing over time (see graph below). Policy tools could be used to mandate or enforce stricter forest restoration obligations after commercial exploration or extraction activities, as well as develop strategies to increase the efficiency of agricultural production. Policymakers could also reward forest conservation activities through financial incentives (more on that later).

2) Improve forest management

Improvements in forest management practices have the potential to significantly improve carbon sequestration from forests (e.g., improved growth strategies; residue management for bioenergy in remote areas, reduced harvest for conservation, better use of harvested wood products, etc.). The Canadian Forest Service has estimated that a suite of best practices could lead to a massive 254Mt of CO2e mitigation on a cumulative basis through 2030.

3) Replanting and regeneration after forest fires

In 2017, Canada experienced 5,611 forest fires, with about 3.4 million hectares burned. Fires are predicted to become an increasingly important driver of land change in the future due to climate change. For example, 2017 was the third year in a row with above-average forest fires.

Forests do typically regenerate after fire. However, if the fires are intense, even the topsoil can be burned away and regeneration can be very difficult. Efforts to accelerate and improve regeneration after fire can result in faster carbon sequestration. For example, much of the federal Low Carbon Economy Fund support for forest carbon sequestration efforts is based on fire scars.

4) Leveraging financing into land-based projects

Many strategies for conserving and regenerating forests and lands require financing that stretches beyond the limits of what governments are able to directly support. As such, innovative financial tools will be needed. Carbon offset credits have been around for a long time and can be used to channel private revenue into land-based projects such as forest restoration or wetland conservation. For example, under the federal Output Based Pricing System, large industrial emitters can purchase offset credits towards compliance obligations rather than paying a direct fee to government or trading with other firms.

As the federal government, and some provinces, are actively working on the design or details of their carbon offset systems, there is an opportunity to leverage mitigation outcomes from Canada’s vast wealth of forests and lands.

Given the scale of the climate challenge – and the potential for land-based projects to deliver additional benefits such as biodiversity conservation – the IPCC report reminds us that the land-sector must be increasingly recognized as a decisive part of our transition to a low-carbon economy.