May 8, 2020

By Mike Moffatt & John McNally

This post is part of Smart Prosperity Institute’s Smart Stimulus Project. To see other posts from this project, click here.

Want to receive the latest analysis and insights on smart stimulus for a resilient economic recovery? Sign up for our monthly updates here.

Today’s release of the April Labour Force Survey data confirms that this economic downturn is unlike anything we have ever seen before in Canada. As such, it will require a new way of thinking and a new set of tools to combat the recession.

Previous recessions

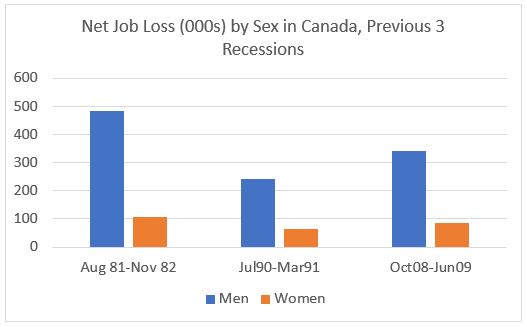

To understand why this recession is different, let’s examine the typical Canadian recession. Here are the net job loss by sex for the last three recessions (as determined by the C.D. Howe Business Cycle Council):

Source: Statistics Canada.

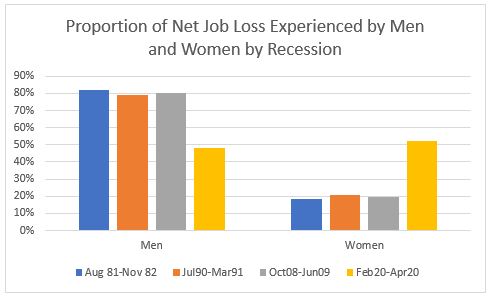

The exact number of jobs lost depends on how you define the start and the end of each recession, but roughly speaking, in the past 3 recessions total employment declined by between 300,000 and 600,000 jobs. The proportion of job loss experienced by men has been incredibly consistent: men experienced 81.8% of the job loss in the 1981-82 recession, 79.3% of the job loss in 1990-91 and 80.3% in 2008-09. The reason for this disproportionate impact on men is straight-forward — goods-producing industries have historically been more sensitive to economic shocks than service-producing ones. Since men are more likely to be employed in goods-producing sectors like manufacturing, they tend to get hit the hardest.

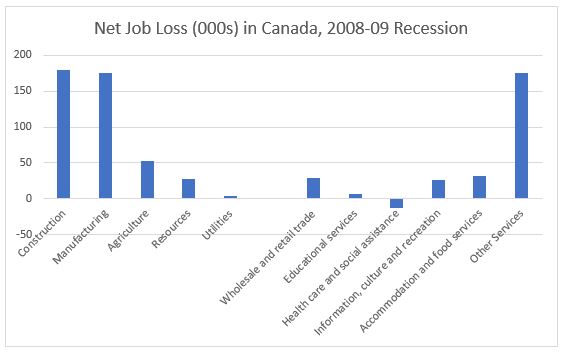

Source: Statistics Canada.

In the months following the financial crisis, over half of the job loss was isolated to two sectors: construction and manufacturing. Nearly two-thirds of all job loss was experienced by Canada’s goods-producing sectors (the ones on the left-side of the above graph), despite those sectors making up less than one-quarter of all Canadian employment. This was not unusual, as the recessions of the 1980s and 1990s had similar sectoral splits.

Because the largest effects of these recessions were felt by men, particularly blue collar men, Canada’s policy responses put a primary focus on finding ways to return them to the workforce, which included an emphasis on infrastructure projects and retraining programs, along with a host of other measures.

The COVID crisis

This recession is substantially different than the last three. First is in scope, as the Canadian economy shed a whopping 2 million jobs in April, after losing more than a million in March. Over the past two months, the number of Canadians with jobs has fallen by 15%, which understates the magnitude as many millions more have seen their hours cut, with many of those still technically employed but not being assigned any hours whatsoever. As well, today’s data release only stretches to mid-April; undoubtedly more jobs have been lost since then. The economic impact around the world may be even larger than the Great Depression, with the Bank of England predicting that United Kingdom GDP will fall by 14% this year, the largest single-year drop since 1706.

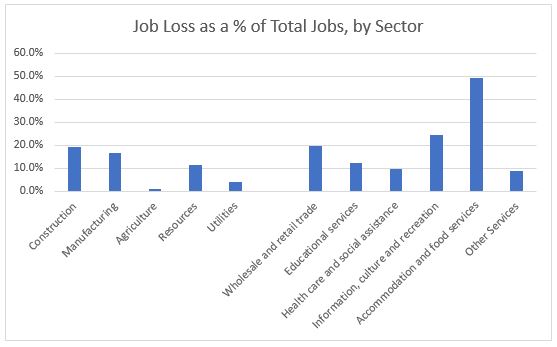

The types of jobs being lost are also different, with a far more proportional split. Of the nearly 3 million net job loss, 80% of those jobs were in services, in line with their proportion of overall jobs. Nearly half of all jobs in accommodation and food services have been lost since the beginning of the crisis.

Construction and manufacturing, which made up over half of all the net jobs lost after the financial crisis, make up less than 20% of the jobs lost since February. Because of the greater proportion of service jobs lost, women are faring worse during this recession, making up 52% of the net job loss, despite being 48% of the workforce. This is in stark contrast to previous recessions.

One other way this recession differs is that the pace of this recovery is about more than creating jobs. Every single recovery scenario comes with the same caveat: “things will return to normal when we defeat COVID-19”. That will not happen until all social restrictions are lifted and consumer confidence fully rebounds. Even if the economy returns to 90% of normal, service and entertainment sectors will need to follow guidelines that will depress revenues and re-hiring for six to 24 months. Many of those jobs will disappear as businesses who could weather six months of closures finally shut down after over a year of inactivity. For those that reopen, they will likely re-hire fewer staff to work fewer hours.

As the economy gradually re-opens, many jobs won’t be around to return to because of business closures or cuts in staff hours. Those looking for work as a result of this will be younger, and are more likely to work in the service sector and be female than in past recessions. Any economic strategy to create jobs must keep them in mind.