April 15, 2021

By Stephanie Cairns and Sonia Cyrus Patel

Smart Prosperity Institute, in collaboration with L’Institut EDDEC, has catalogued real-world strategies and practices supporting the transition to a circular economy for seven key sectors in the Canadian economy. This research, which is being released one sector at a time in a series entitled Circular Economy Global Sector Best Practices, aims to provide a starting point in the journey towards building Canadian sector roadmaps to a circular economy.

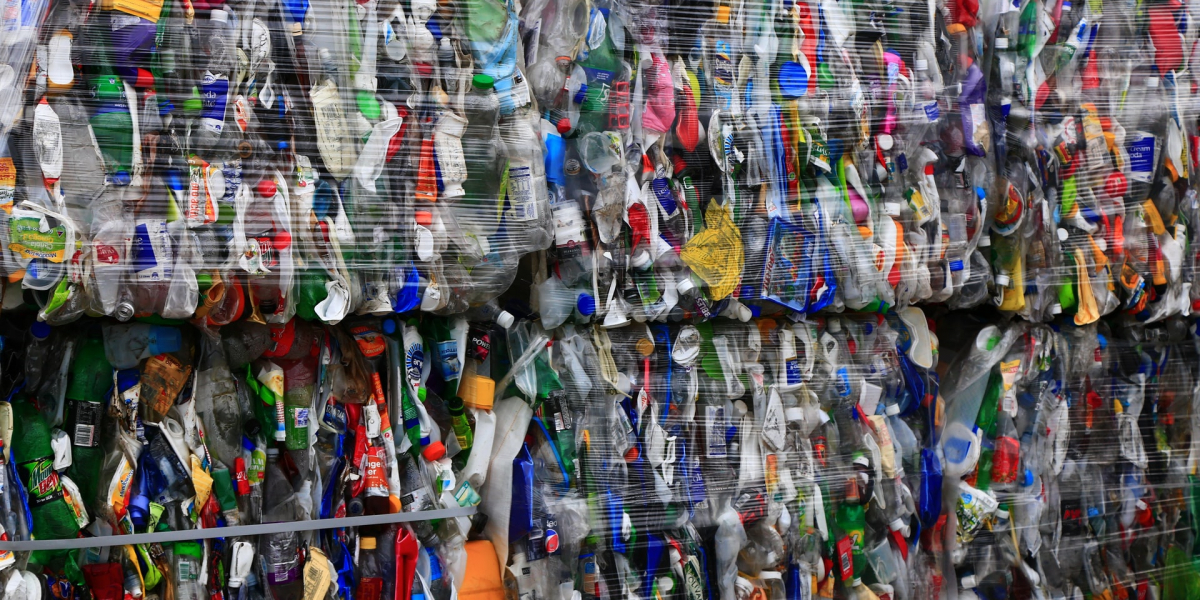

Plastics pollution is one of the most pressing challenges of our time. Our oceans already contain over 150 million tonnes of plastics, with an annual increase of 8 million tonnes.1 Should this trend continue, the ocean would contain one tonne of plastic for every three tonnes of fish by 2025, and more plastics than fish by weight by 2050.2 The quantum of plastic entering our environment is a direct result of the linear plastic economy. In Canada for example, only 9% of plastics was recycled in 2016, while 86% was sent to landfill – representing a lost economic value of C$7.8 billion.3

Moving towards a circular plastics economy requires innovation on both the upstream and downstream stages of a product’s lifecycle. Upstream innovation focusses on redesigning products, materials, and services to prevent the creation of plastic waste in the first place, while downstream innovation works on improved recycling and composting systems and technologies, as well as establishing stable markets for post-consumer plastics.

Consumers like the idea of compostable packaging, and for this reason the use of bioplastics as a substitute for petroleum-based packaging is gaining momentum. However the introduction of these new materials into the packaging stream illustrates the need for upstream and downstream transitions to go hand in hand.

Examples of bioplastics include BioPBS (bio-based polybutylene succinate) plastic created by Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation, derived from natural resources such as sugarcane cassava and corn, which is biodegradable and can be composted into biomass, carbon dioxide and water.4 Another example is Bio-on’s Minerv-PHA (Polyhydroxyalkanoates), a second-generation bioplastic created from biomass waste such as by-products and waste from sugar beet, sugar cane, glycerol from biodiesel, potatoes, animal fat, fruit, vegetables, wood, domestic wet waste and wine production. It is also biodegradable in soil and marine biodegradable.5 Bioplastics have many diverse and mainstream applications. The Coca-Cola Company for instance sells soda in “PlantBottles” made of plastic derived from plant sugars. Ford Motors has been using soy-based plastics to make parts for its cars since 2007.6

While the substitution of renewable, compostable plastics ticks many criteria for a circular plastics economy, in practice the introduction of bioplastics into post-consumer waste streams presents many challenges for current recycling and composting collection, sorting, and processing systems. For example, bioplastics collected alongside petroleum-based plastics are difficult to separate out, and can contaminate entire lots of recycled plastics. Yet the alternative, of collecting bioplastics within municipal organic collection programs, is equally problematic. Few municipal composting facilities operate at the high temperatures or with the extended retention times needed to actually compost most bioplastics, and additionally, smaller facilities designed primarily for food scraps could easily be overwhelmed by growing quantities of bioplastic packaging. Until collection systems and infrastructure are redesigned to better service this different bioplastic waste stream, its environmental promise will not be realized.

While the plastics sector still has a long way to go on its path to circularity, bioplastics and many more promising practices are an encouraging sign of things to come. If you’re interested in learning more about circular strategies and practices currently being employed in the plastics sector, you can find them in the fifth part of the Circular Economy Global Sector Best Practices.

The series also covers circular economy best practices in six other sectors of the Canadian economy. Stay tuned for the sixth part of the series, profiling the bio-economy sector, which will be published in May 2021.

1 World Economic Forum, Ellen MacArthur Foundation, & McKinsey & Company. (2016). The New Plastics Economy — Rethinking the future of plastics.

2 World Economic Forum, Ellen MacArthur Foundation, & McKinsey & Company. (2016). The New Plastics Economy — Rethinking the future of plastics.

3 Deloitte, Cheminfo Services Inc., & Environment and Climate Change Canada. (2019). Economic Study of the Canadian Plastics Industry, Markets and Waste – Summary Report to Environment and Climate Change Canada.

4 MCPP. (n.d). BioPBS.

5 Bioplastics News. (2019). Best Bioplastic Company of 2019.

6 Science History (n.d). Science Matters: The Case of Plastics.